New York, NY, March 11, 2020

Organizing author: Viktor Sander, B.Sc., B.A. | Contributing authors: Suzanne Degges-White, Ph.D., Hannah Rose, L.C.P.C., Tara Well, Ph.D., Sean Seepersad, Ph.D., Dr. Peter J. Helm, Lara Otte, Psy.D., Rebecca A. Housel Ph.D., Andrea Brandt Ph.D. M.F.T., Romeo Vitelli Ph.D., M.S., Kyle D. Pruett M.D., Timothy Matthews Ph.D. | Commentary and insight: Christina R. Victor, B.A., M Phil, Ph.D., Prof. Mike Z. Yao, Melissa G. Hunt, Ph.D. | About the authors.

Despite millennials being twice as lonely as baby boomers, almost all research to date has focused on baby boomers. This report presents several proposals to tackle millennial loneliness.

A 2019 study conducted by the insurance company Cigna found that younger generations are lonelier than older generations.[1] A 2018 UK national survey found that 22% of millennials report having no friends and that 30% often feel lonely. In comparison, 15% of baby boomers report that they often feel lonely.[2]

This report sets out to review studies on loneliness between 2010 and 2020 to find actionable ways to tackle millennial loneliness.

At a Glance

Findings on Millennial Loneliness

- Despite loneliness being twice as common among millennials as among the elderly, almost all research has focused on the elderly.

- Social media makes social people more social and lonely people more lonely.

- Millennial loneliness is different from loneliness among the elderly and needs other solutions.

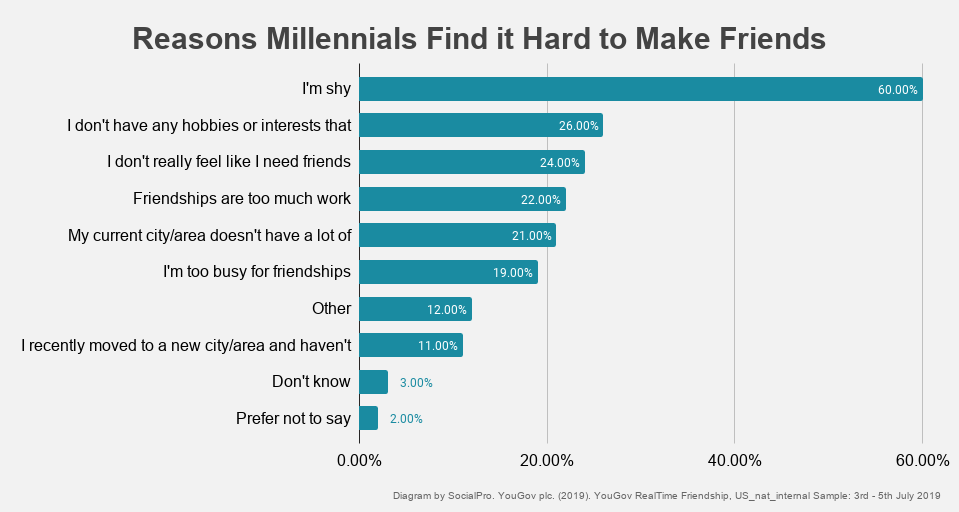

- Sixty percent of millennials who find it difficult to make friends say it’s because they’re shy.

- The overall mental health of U.S. Adolescents and young adults has deteriorated since the mid-2000s.

- An increase in single households doesn’t seem to cause loneliness—but bad city planning does.

What We Can Do As a Society

- Detect shyness in children early with prevention and intervention programs.

- Encourage at-risk individuals to replace social media use with real-life interactions.

- Avoid the medicalization of loneliness.

- Adopt standardized measures of loneliness for regular health checkups.

- Plan cities in a way that promotes social connection.

- Reduce the stigma attached to loneliness.

What We Can Do As Individuals

- Look for ways to increase your social interaction in day-to-day life, even if it feels uncomfortable.

- Use social media to connect rather than to compare.

- Substitute screen time with real-life social interaction.

- Make a plan for how to spend your free time.

- Consider taking up a social hobby.

- Volunteer.

- Be aware of how you see and relate to yourself.

- Open up to build meaningful emotional connections.

- Practice acceptance to overcome existential loneliness.

Findings on Millennial Loneliness

1. Despite Loneliness Being Twice as Common Among Millennials as Among the Elderly, Almost All Research Has Focused on the Elderly

The UK government commissioned the What Works Centre for Wellbeing to find ways to mitigate loneliness.[3] After reviewing 364 studies, they discovered that there wasn’t enough data on loneliness intervention among the young. Instead, they had to base their recommendations on findings from studies made on people 55 years and older.

2. Social Media Makes Social People More Social and Lonely People More Lonely

A report published in Information, Communication & Society shows that social media can both increase or decrease our social well-being depending on how we use it.[4]

In a research article published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, the authors propose that loneliness is a determinant of how people interact with the digital world. Individuals who do not identify as lonely use social media to connect and make new friends. Lonely individuals can use it as a substitute for real-life social interaction. This can make lonely individuals feel more isolated.[5]

Dr. Melissa G. Hunt led a study published in the Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology on the link between social media and loneliness.[8] She explains:

Social media can be a source of connection for people – it just depends on how you use it, and how much time you spend on it. Using social media for less than one hour a day, to stay connected to true friends, is associated with increased well-being, and less loneliness and depression. Using social media for more than an hour a day, and following lots of “strangers” (influencers, celebrities) is associated with increased loneliness and depression.

3. Millennial Loneliness Is Different from Loneliness Among the Elderly and Needs Other Solutions

Loneliness among the elderly is often caused by the loss of a life partner or reduced social contact.[6] Millennial loneliness is less researched.[3] It likely has many different causes, which could include:

- Shyness

- Social anxiety

- Low self-esteem

- Depression

- Differing interests from others

- Homesickness

- Social isolation

- Emotional isolation

- Existential worries

Emotional loneliness is typically related to relationships with significant others in your life (relationship partners, attachment figures, etc.) while social loneliness is typically related to one’s broader social network and friend groups.[29]

Existential loneliness is characterized by the awareness that everyone is on their own in this world, regardless of family, friends, or others in our support networks.[40]

4. 60% of Millennials Who Find it Difficult to Make Friends Say It’s Because They’re Shy

A survey by YouGov Omnibus found that 60% of millennials who find it difficult to make friends say it’s because they are shy.[1] 26% of that group say they don’t have hobbies or interests that facilitate friendships, and 24% say they feel like they don’t really need friends.

Because of the overrepresentation of shyness, it becomes an important factor in tackling millennials’ loneliness.

The diagram shows what millennials who find it difficult to make friends think is their biggest obstacle to making friends. 60% of these millennials say it’s because they’re shy.[7]

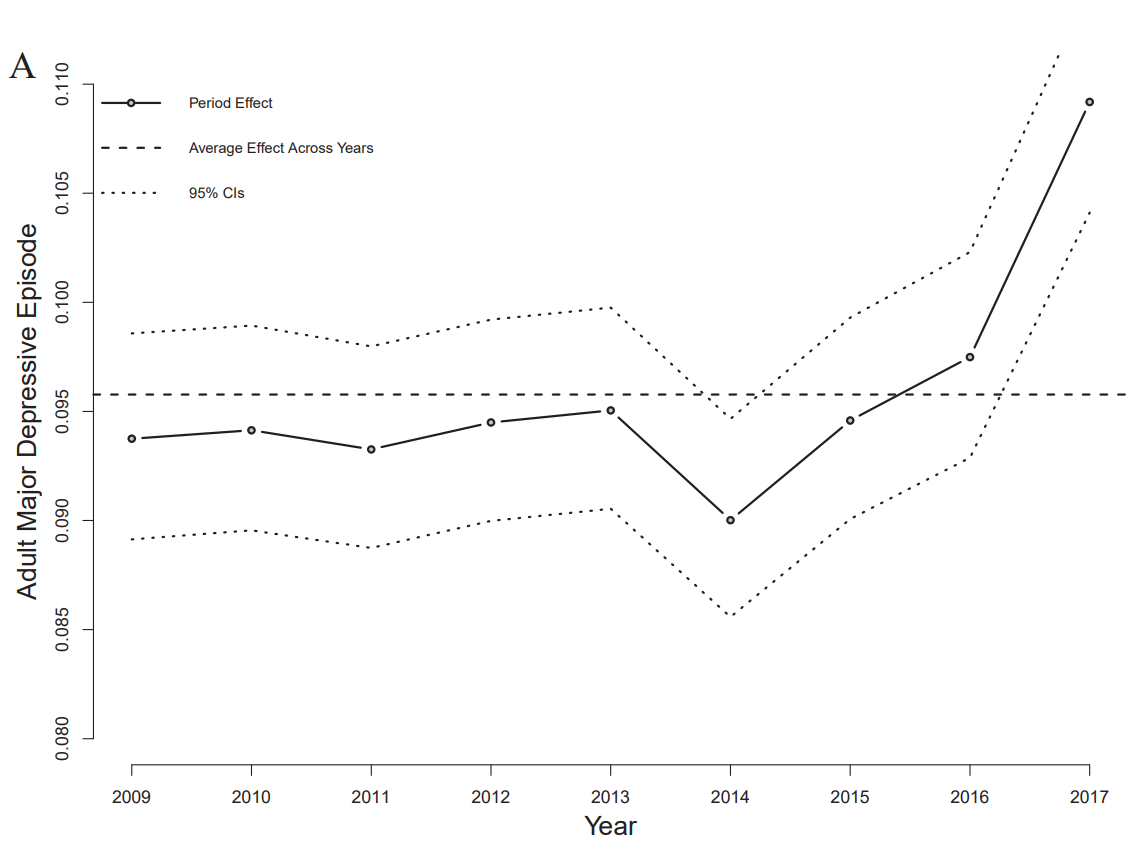

5. The Overall Mental Health of U.S. Adolescents and Young Adults Has Deteriorated Since the Mid-2000s

Psychological distress, major depression, suicidal thoughts, and suicides have increased in U.S. adolescents and adults since the mid-2000s.[32] There has been no comprehensive study of loneliness across age groups prior to 2018.[3]

Percent of young adults with serious psychological distress 2008 –2017 in age-period-cohort analyses. Diagram from Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

Professor Christina R. Victor was commissioned by the UK government to study loneliness interventions. She explains:

The data from a national survey published in 2018 is the first robust one looking at loneliness across the age groups. What we don’t know is if loneliness always has been high in young adults and we just didn’t bother to ask. So we can’t be certain that loneliness among young adults is a “new problem” or was always there—so blaming social media is an easy but lazy explanation.

6. An Increase in Single Households Doesn’t Seem to Cause Loneliness—but Bad City Planning Does

In 2016, 28 percent of US households had just one person living in them – an increase from 13 percent in 1960.[9] However, there’s no clear evidence that living alone makes us lonelier.[10]

Ample evidence, however, indicates that city planning affects loneliness. It’s important to create public spaces people want to spend time in and meet in.[11][43]

What We Can Do As a Society

Below, this report presents 6 recommendations on what can be done on a societal level to tackle millennial loneliness.

1. Detect Shyness in Children Early With Prevention and Intervention Programs

Shyness and having few friends are strongly connected.[7] Addressing shyness in children early can help prevent adverse outcomes later in life.[12]

2. Encourage At-risk Individuals to Replace Social Media Use With Real-life Interactions

While social media isn’t the root cause of loneliness, it can exacerbate loneliness in individuals who are already lonely.[4] At-risk individuals can benefit from limiting their social media use.[8] This can be encouraged through schools or public information campaigns directed at parents or social media users.

3. Avoid the Medicalization of Loneliness

Loneliness and its far-reaching consequences have been overlooked by the medical community.[13] Furthermore, medicine likely lacks effective tools to address many of the complex causes of loneliness.[33] There is a risk that medicalization may trivialize some of those causes of loneliness.

Loneliness often emerges in the context of other co-occurring difficulties, like mental health problems, unemployment, bad experiences in childhood, or changing life circumstances. If someone is lonely, mental health professionals need to be aware that they might also be struggling in multiple areas of life. This bigger picture needs to be taken into account.

There are new methods on the rise that could help expand the toolboxes of mental health professionals, such as the use of social prescriptions—prescribing social activities as an alternative or complement to medication.[14]

4. Adopt Standardized Measures of Loneliness for Regular Health Checkups

The U.K. has adopted a nationwide measurement of loneliness.[15] Questions being asked at health checkups include:

- How often do you feel lonely?

- How often do you feel that you lack companionship?

- How often do you feel left out?

- How often do you feel isolated from others?

A standardized measure can provide a better understanding of loneliness and its relationship to patients’ other medical issues.

5. Plan Cities in a Way That Promotes Social Connection

A study published in The Lancet highlighted how city planning affects health and social interaction.[11] The UK’s minister of loneliness announced plans in 2018 to improve UK city planning, encouraging people to interact. Well-designed formal public places such as town squares, plazas, parks, gardens, and informal places such as streets, spaces between buildings, and bus stops facilitate human interaction.[16]

6. Reduce the Stigma Attached to Loneliness

Many young people don’t want to admit to feeling lonely.[35] Sometimes they feel it can be perceived by others as a personal failing or character flaw. We should make loneliness part of the current discussions around mental health, and increase awareness that it’s a common problem for young people. Suffering in silence could itself be part of the problem.

Loneliness is not always pathological. For many, it’s something temporary that resolves in due course as people’s circumstances change. This is particularly true for young people, who are going through life transitions.[35]

Some researchers argue that loneliness serves a purpose,[36][37] by giving people the motivation to re-connect with others – like the sensation of hunger motivates us to keep feeding ourselves.

Informing about and encouraging discussion about a topic are effective ways to help alleviate stigma associated with it.[39]

What We Can Do As Individuals

Below, this report presents 9 recommendations on what can be done on an individual level to tackle millennial loneliness.

1. Look for Ways to Increase Your Social Interaction in Day-to-day Life, Even If it Feels Uncomfortable

As described in the findings section above, 60% of millennials who find it hard to make friends say it’s because they’re shy. Exposing yourself to situations you find uncomfortable can help you overcome social anxiety or shyness.[17]

Here are some examples of ways to get more social exposure:

- Take micro-steps rather than trying to be more social overnight. Adopt behaviors that are new to you, but not terrifying.

- Make it a habit to smile when greeting someone.

- Accept invitations as often as you can.

- Engage socially and put your phone away, even if you’d feel more comfortable looking at your phone.

- Take the initiative to meet up with someone even if you fear rejection.

- Make small talk with the cashier or bus driver.

2. Use Social Media to Connect Rather Than to Compare

Not all social media use increases loneliness. But when social media is used to compare oneself with others or as a replacement for real-life social interaction, it can have a negative effect on well-being.[18] When used to connect with others, it can have positive effects on one’s social life.[4]

Use social media primarily to facilitate a more active social life and to maintain important relationships.[19]

Examples of beneficial uses of social media:

- Message your friends to meet up or plan an event.

- Keep in touch with your relatives on the other side of the country.

- Find meetups and groups that interest you.

If you notice that you use social media to compare yourself to others, see if you can unfollow accounts that make you feel bad. Remind yourself that what you see on social networking sites doesn’t necessarily reflect someone’s real life.

3. Substitute Screen Time With Real-life Social Interaction

If you use social media for comparing, as described in the previous step, you can benefit from limiting screen time. In a study published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, participants were instructed to limit their screen time to 30 minutes a day.[8] Compared to a control group without limits, the group limiting their social media use showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over a three-week period. Another study showed that the mere presence of a cell phone during a real-life interaction has negative effects on closeness, connection, and conversation quality.[20]

Mobile applications that can help limit screen time:

- If you use an iPhone, you can use Apple’s proprietary app Screen Time.

- If you use Android, Google has developed a suite called Digital Wellbeing.

- More app recommendations here. This report does not endorse any app. Do your due diligence before installing something on your phone.

Dr. Mike Yao, author of the study “Loneliness, Social Contacts, and Internet Addiction: A Cross-Lagged Panel Study,” explains:

Shared experience trumps connectivity in building meaningful social relationships. Pen pals living far apart and only sending each other letters once a month can become best friends if they read the same books, see the same TV shows, and share the same hobbies. Two colleagues can see each other every day and chat every time they see each other, but if the only shared reality between them is their job, they would never become friends. Today, people are communicating more with others and their social networks are expanding, but they are increasingly living in their own isolated social realities.

4. Make a Plan for How to Spend Your Free Time

Prepare a strategy for what to do when you are not using your phone. While interaction with technology is instant, real-life social interaction usually takes some form of planning. Create a habit to make plans with friends.

Examples of social activities to plan:

- Text friends a few days in advance to propose an activity.

- Propose doing school- or work-related activities together rather than apart.

- Look for events in your city and invite friends to join.

- Do outdoor activities such as playing sports or taking a walk.

- Eat lunch or dinner with friends rather than eating alone.

5. Consider Taking up a Social Hobby

A social hobby can help alleviate loneliness and increase well-being.[21][22] However, there’s been an overall decline in recreational activities since the 1960s.[23]

Social hobbies can help alleviate loneliness. Some examples are:

- Dancing

- Writing

- Cooking classes

- Group hiking

- Book clubs

- Running clubs

These types of activities can be found at websites such as Meetup.com, Eventbrite.com, or by using Facebook’s group search.

6. Volunteer

Only 1 in 5 millennials volunteer, but 1 in 3 adults in Generation X (those born between 1965 to 1980) give their time to charitable causes[24]. Volunteering and philanthropy have been shown to reduce loneliness and have positive effects on well-being.[25][26][27][28]

Below you’ll find 3 resources for US citizens. You can also Google “volunteering” and the name of your city for local opportunities.

7. Be Aware of How You See and Treat Yourself

Emotional loneliness is different from social loneliness: individuals who are not alone can still feel lonely.[29] Studies show that emotional loneliness can be improved with mindfulness and self-compassion.[30]

Established methods to practice mindfulness and self-compassion include:[31]

- Reminding yourself that everyone experiences loneliness and suffering from time to time.

- Talking to yourself like you would talk to a friend you care about.

- Accepting thoughts and feelings that come up rather than trying to change or remove them.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an intervention that helps change how someone thinks about themselves, others, and social interactions.[41] It’s proven effective for reducing loneliness. Working with a professional trained in the use of CBT can help lead you through the process. If you do not have access to a therapist, a CBT-based book can be effective.[42]

8. Open up to Build Meaningful Emotional Connections

To develop close bonds, we need to disclose things about ourselves. Self-disclosure helps make those around you comfortable with sharing about themselves, too. Getting to know each other on a personal level helps expedite feelings of closeness.[38]

Some things you can do to self-disclose:

- Share small things about yourself, your thoughts and opinions. You don’t have to disclose sensitive information.

- If someone asks how you’re doing, share a little bit about what you’ve been up to.

- Share your emotional state when appropriate. “I feel a little nervous before the finals, how are you feeling?”

9. Practice Acceptance to Overcome Existential Loneliness

Existential loneliness differs from social and emotional loneliness. It’s a feeling characterized by the awareness that everyone is on their own in this world, regardless of family, friends, or others in our support networks.[40] Existential fears include the fears of isolation, death, or meaninglessness.

Two things that can alleviate existential loneliness:

- Accept existential thoughts and feelings rather than trying to change or stop them. Let realizations of existentialism and the end of things be a motivation to live life more fully.

- Recognize that everyone is struggling to make sense of their lives, to live a meaningful life, and to exist in such a way that their lives matter. Reminding yourself that you are not alone in your struggles can help normalize and relieve existential anxiety.

References

-

- Cigna. (2018). Cigna 2018 US Loneliness Index.

- Ballard, J. (2019). Millennials are the loneliest generation. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Victor, C., Mansfield, L., Kay, T., Daykin, N., Lane, J., Duffy, L. G., … & Meads, C. (2018). An overview of reviews: the effectiveness of interventions to address loneliness at all stages of the life-course. London, UK: What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

- Hall, J. A., Kearney, M. W., & Xing, C. (2019). Two tests of social displacement through social media use. Information, Communication & Society, 22(10), 1396-1413.

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world?. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 70-87.

- Savikko, N., Routasalo, P., Tilvis, R. S., Strandberg, T. E., & Pitkälä, K. H. (2005). Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 41(3), 223-233.

- YouGov plc. (2019). YouGov RealTime Friendship, US_nat_internal Sample: 3rd – 5th July 2019 [Data set]. Retrieved February 28, 2020 from https://d25d2506sfb94s.cloudfront.net/cumulus_uploads/document/m97e4vdjnu/Results%20for%20YouGov%20RealTime%20%28Friendship%29%20164%205.7.2019.xlsx%20%20%5BGroup%5D.pdf

- Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751-768.

- US Census Bureau. (2016). The majority of children live with two parents, Census Bureau reports. United States Census Bureau Newsroom. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Jamieson, L., & Simpson, R. (2013). Living alone: Globalization, identity and belonging. Springer.

- Giles-Corti, B., Vernez-Moudon, A., Reis, R., Turrell, G., Dannenberg, A. L., Badland, H., … & Owen, N. (2016). City planning and population health: a global challenge. The Lancet, 388(10062), 2912-2924.

- Rubin, K. H., Bowker, J. C., & Gazelle, H. (2010). Social withdrawal in childhood and adolescence. In K. H. Rubin & R. J. Coplan (Eds.), The development of shyness and social withdrawal (pp. 131–156). New York: Guilford Press.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet, 391(10119), 426.

- Fowler, Kimberly. “Could We See More Patients Receive ‘Social Prescriptions?’.” Next Avenue, 14 May 2019, www.nextavenue.org/patients-receiving-social-prescriptions/. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Birnstengel, Grace. “What Has U.K.’s Minister of Loneliness Done to Date?” Next Avenue, 16 Jan. 2020, www.nextavenue.org/uk-minister-of-loneliness/. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Thompson, S., & Kent, J. (2014). Connecting and strengthening communities in places for health and well-being. Australian Planner, 51(3), 260-271.

- Anthony, M Martin, Swinson, Richard P. (2008). The Shyness & Social Anxiety Workbook Second Edition pp. 143-201. Oakland, CA

- Saiphoo, A. N., Halevi, L. D., & Vahedi, Z. (2020). Social networking site use and self-esteem: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, 109639.

- Manago, A. M., & Vaughn, L. (2015). Social media, friendship, and happiness in the millennial generation. In Friendship and happiness (pp. 187-206). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2013). Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 237-246.

- Pressman, S. D., Matthews, K. A., Cohen, S., Martire, L. M., Scheier, M., Baum, A., & Schulz, R. (2009). Association of enjoyable leisure activities with psychological and physical well-being. Psychosomatic medicine, 71(7), 725.

- Conner, T. S., DeYoung, C. G., & Silvia, P. J. (2018). Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(2), 181-189.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). Volunteering in the United States, 2015. USDL 16-0363.

- Smith, J. M. (2012). Toward a better understanding of loneliness in community-dwelling older adults. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 293-311.

- Choi, N. G., & Kim, J. (2011). The effect of time volunteering and charitable donations in later life on psychological wellbeing. Ageing & Society, 31(4), 590-610.

- Molsher, R., & Townsend, M. (2016). Improving wellbeing and environmental stewardship through volunteering in nature. EcoHealth, 13(1), 151-155.

- Konrath, S. (2014). The power of philanthropy and volunteering. Wellbeing: A complete reference guide, 1-40.

- Van Baarsen, B., Snijders, T. A., Smit, J. H., & Van Duijn, M. A. (2001). Lonely but not alone: Emotional isolation and social isolation as two distinct dimensions of loneliness in older people. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(1), 119-135.

- Akin, A. (2010). Self-compassion and Loneliness. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(3).

- Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self‐compassion in clinical practice. Journal of clinical psychology, 69(8), 856-867.

- Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

- McLennan, A. K., & Ulijaszek, S. J. (2018). Beware the medicalisation of loneliness. The Lancet, 391(10129), 1480.

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219-266.

- Snape, D., & Manclossi, S. (2018). Children’s and young people’s experiences of loneliness: 2018, London.

- DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., & Rouby, D. A. (2009). Social exclusion and early-stage interpersonal perception: Selective attention to signs of acceptance. Journal of personality and social psychology, 96(4), 729.

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

- Aron, A., Melinat, E., Aron, E. N., Vallone, R. D., & Bator, R. J. (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 363-377.

- Sciences, S., & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Approaches to Reducing Stigma. In Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change. National Academies Press (US).

- Bolmsjö, I., Tengland, P. A., & Rämgård, M. (2019). Existential loneliness: An attempt at an analysis of the concept and the phenomenon. Nursing Ethics, 26(5), 1310-1325.

- Beck JS (2011), Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.), New York, NY: The Guilford Press, pp. 19–20.

- King, R. J., Orr, J. A., Poulsen, B., Giacomantonio, S. G., & Haden, C. (2017). Understanding the therapist contribution to psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analytic approach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 664-680.

- Gibney, S., Moore, T., & Shannon, S. (2018). Investigating the role of age-friendly environments in combating loneliness in Ireland. European Journal of Public Health, 28(suppl_4), cky213-209.

About the authors

Organizing author

Viktor Sander B.Sc., B.A. Scientific review board manager at SocialSelf. Author profile

Contributing authors

Suzanne Degges-White, Ph.D., Chair and Professor, Counseling and Counselor Education, Northern Illinois University. Author profile

Kyle D. Pruett M.D., Clinical Professor in the Child Study Center at the Yale School of Medicine. Author profile

Tara Well, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Psychology, Barnard College of Columbia University. Author profile

Sean Seepersad, Ph.D., Adjunct Professor in Human Development and Family Sciences, UCONN. Founder of the Web of Loneliness Institute. Author profile

Hannah Rose, L.C.P.C., Clinical therapist. Author profile

Dr. Peter J. Helm., Postdoctoral Fellow at The University of Missouri. Author of the study Existential isolation, loneliness, and attachment in young adults. Author profile

Lara Otte, Psy.D., Psychologist and Executive Coach. Author profile

Rebecca A. Housel Ph.D., Editorial Advisory Board for the Journal of Popular Culture and the Journal of American Culture. Author profile

Andrea Brandt Ph.D. M.F.T., Practicing therapist. Author profile

Romeo Vitelli Ph.D., Practicing psychologist. Author profile

Timothy Matthews, Ph.D., British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at King’s College London. Author of the study Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Author profile

Commentary and insight

Melissa G. Hunt, Ph.D., Associate Director of Clinical Training in the Department of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. Author of the study No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression.

Prof. Mike Z. Yao, Professor & Head at The Charles H. Sandage Department of Advertising, College of Media. Author of the study Loneliness, social contacts and Internet addiction: A cross-lagged panel study. Author profile

Christina R. Victor Ph.D., Vice Dean Research / Professor at Brunel University London. Research on loneliness. Author profile

About SocialSelf

SocialSelf is one of the largest websites covering social skills and social psychology. The company works together with psychologists and doctors to provide actionable, well-researched and accurate information that helps readers improve their social lives.

SocialSelf was founded in 2012. Today, they have 250 000 monthly visitors. Visit SocialSelf here.

Disclaimer

Our content is not a substitute for professional advice from a psychologist, therapist, doctor, or any other healthcare provider. Don’t disregard any advice you’ve received from your healthcare provider because of something you’ve read in this report or anywhere else on socialself.com.

All the information on this website—socialself.com—is published in good faith and for general information purposes only. SocialSelf does not make any warranties about the completeness, reliability, and accuracy of this information. Any action you take upon the information you find on this website or in this report is strictly at your own risk. SocialSelf will not be liable for any losses and/or damages in connection with the use of our website.

From this report and from our website, you can visit other websites by following hyperlinks to such external sites. While we strive to provide only quality links to useful and ethical websites, we have no control over the content and nature of these sites. These links to other websites do not imply a recommendation for any of the content found on these sites. Site owners and content may change without notice and may occur before we have the opportunity to remove a link that may have gone “bad.”

Be aware that when you leave our website, other sites may have different privacy policies and terms that are beyond our control. Please be sure to check the privacy policies of these sites as well as their terms of service before engaging in any business or uploading any information.