Depression is an incredibly common mental illness. Approximately 20% of adults worldwide will experience depression at some point in their life.[1] Someone in your life will most likely develop depression, so what can you do to help?

Talking to someone with depression and encouraging them to tell you how they’re feeling can support their recovery. It’s also difficult. You’re probably worried about your loved one and trying to talk to them in constructive ways to avoid making them feel worse.

We’re going to give you the information you need to help you support someone with depression and encourage them to get the help they need.

- How to talk to someone with depression

- What not to say to someone with depression

- Types of depression

- Suicide prevention

- How to look after yourself

- Common questions

How to talk to someone with depression

No matter how much we want to help, it can be hard to know how to talk to someone about their mental health. Here are some of the most important things to keep in mind that will let you talk supportively to someone with depression.

1. Ask how they are feeling

Asking about their emotions is the first step. People with depression (especially men) often believe that other people don’t care about their feelings, so asking the question (and making it clear that you care about the answer) lets them talk.[2]

They may shrug off your initial inquiry, for example by saying “fine.” You can follow up with a gentle question, such as “Is that a real ‘fine,’ or a just being polite ‘fine’?” This lets them talk if they want to, without too much pressure.

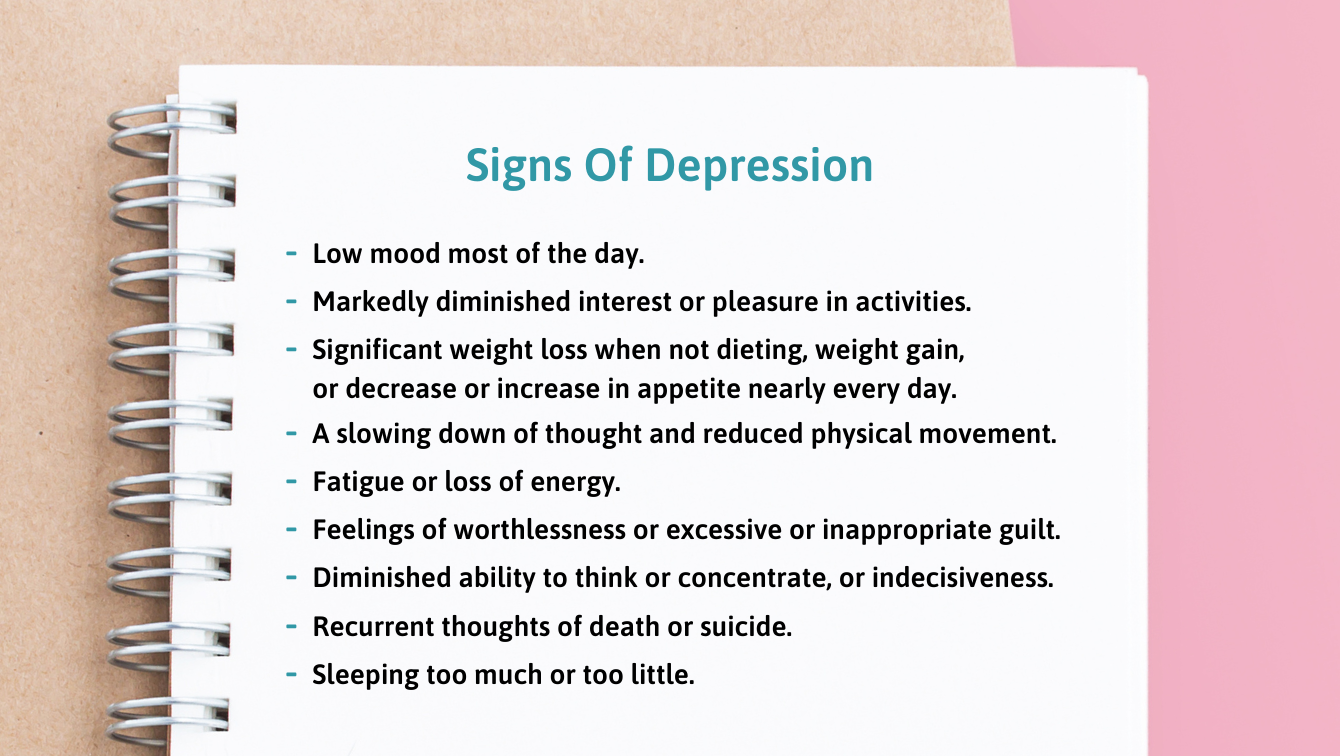

2. Be informed

People with depression might not have the energy or resilience to look up their symptoms and understand what’s wrong.[3][4] It can be helpful for you to understand as much as possible about what might be going on for them.

Understanding more about depression lets you explain that the things they are experiencing are completely normal.

For example, lots of people with depression will struggle with an Impossible Task. This is when a seemingly easy task, such as opening the mail or making the bed, starts to feel overwhelming. This can make them feel inadequate or stupid.

Understanding Impossible Tasks lets you gently explain that this isn’t a sign of weakness, which can make it easier for the depressed person to accept help.

3. Try to understand, not change, their feelings

This one’s tough. When you are talking to a friend with depression, or a loved one, you probably want to make it all OK. You might think:

“I hate that someone I love is suffering. I want to wrap them in my love and care and make them happy. If I love them enough, surely I should be able to do that.”

Realizing that you can’t “fix” their depression can feel awful.

As hard as it might be to accept, working to understand their emotions is often the best thing you can do.

One small caveat is that it’s not the depressed person’s job to help you understand. Make space for them to speak, let them know that you’re happy to listen, but avoid anything that might feel like an interrogation. Try saying, “I’d like to understand as much as you’re comfortable telling me.”

4. Let them know you have a support network

People with depression typically feel a lot of guilt for not being able to “snap out of it,” struggling with normal tasks, and being a burden on people who offer to help.[5]

Try to limit their guilt around asking for support by showing them that you have others ready to support you.

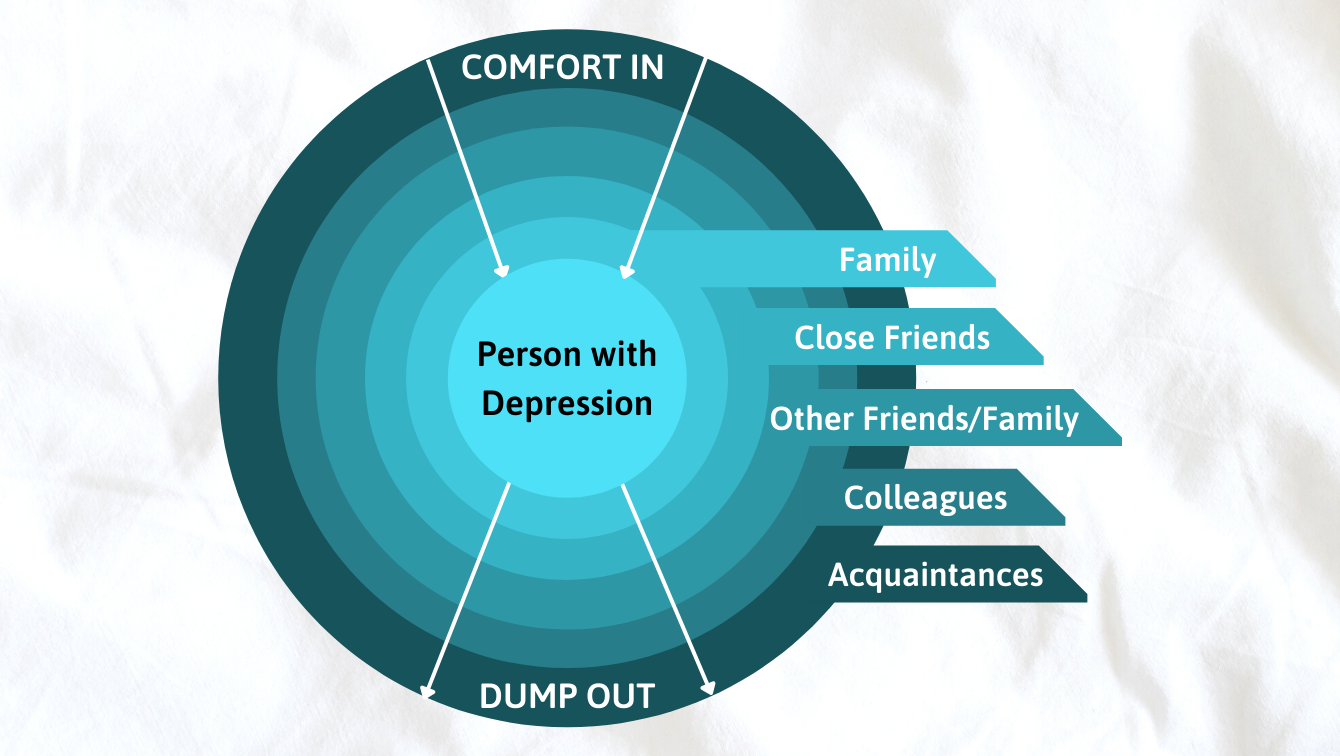

It can be helpful to explain the idea of the Ring Theory as a way of helping someone in need. The person who is suffering most (in this case, the person with depression) is at the center. Around them is a “ring” made up of the people closest to them, for example, their spouse, child, or parent. The next ring might be close friends and extended family.

Each ring offers support and comfort to anyone in a ring that’s smaller than their own and gets to ask for support from anyone in a larger ring.

Showing someone with depression that you’re looking after yourself can make it easier for them to open up.

5. Don’t ask for quick decisions

One symptom of depression is difficulty making decisions, especially if put on the spot.[6] This can lead people to reject offers of help when they would actually appreciate it.

Make this easier by saying, “You don’t need to decide now.” This reduces the pressure and lets the other person think about whether they would like help in their own time.

You can also phrase questions in a way that makes it easier for them to decide. For example, “What would you like to do?” can feel like a lot of pressure. Try “How about we go for a walk?” instead.

6. Show them they’re not alone

Depression is lonely. It can feel as though no one would ever want to spend time with you and that no one could possibly understand.[7] Finding ways to demonstrate that they’re not alone can really help.

Simply telling someone that you’re happy listening to them and that you don’t want them to go through this alone can be deeply meaningful. Telling them that you’re only a phone call away or sending them a text to let them know that you’re thinking of them lets them feel like you really care.

Most importantly, follow through on the things you offer. People with depression often think that others are “just being nice” and that they don’t really care. This can make them hypersensitive to missed plans or offers of help that fall through.[8] It’s often better to under-promise and over-deliver than the other way around.

These statistics on depression in the US can also be enlightening.

7. Remind them that this isn’t their fault

People with depression are prone to blaming themselves for problems, even things they couldn’t possibly be responsible for.[9] They typically blame themselves for their depression

They may call themselves “weak”, “pathetic,” or “failures” for not feeling happier and believe that they are an unacceptable (and unwelcome) burden on the people who love them.[10]

Remind them that having depression isn’t a moral failing or a sign of weakness. It’s an illness that comes from a combination of biological (including genetic) and environmental factors.[11] They’re no more at fault for having depression than they would be for having an allergic reaction or a broken arm.

It can sometimes help to point out that depression is a very common illness, and they are not alone in facing these difficulties. You could explain that it’s really common for people with depression to struggle with domestic chores and personal care such as showering. Be careful with this, though. It’s important that your loved one feels that you are responding to them as an individual and not trivializing their problems.

For example, saying “people with depression usually get behind on their housework” can sound dismissive. Instead, try

“Depression can make it difficult for people to do things they’d normally find easy. If you feel like that, it’s not your fault. It’s part of how the illness works. For example, you might feel really sick at the thought of doing the vacuuming or the laundry. If that happens, I’m not going to judge you. It’s OK. I can help.”

8. Work with them to seek help

Helping someone with depression isn’t about trying to fix everything yourself. It’s just as important that they seek help from professionals.

There are many different types of help available, and it can be helpful for them to talk to their doctor about what is likely to be most effective.[12]

It’s important not to push one type of treatment if they aren’t completely comfortable with it. For example, you might have had a great response to antidepressants, but they might feel wary of taking medication. Alternatively, they might not feel able to open up to someone in therapy and prefer to try medication first.

Although depression can make it difficult to make decisions, it’s essential that your loved one feels in control of their treatment.[13] Consider offering to come with them to a medical appointment (but don’t insist), or asking if they’d like you to call and make the appointment.

Ultimately, show your loved one that you take what they’re telling you seriously, you’ll respect their wishes, and that you want to help them find help that they can accept.

What not to say to someone with depression

Although saying something is definitely better than avoiding talking about depression, there are some comments that can make things more difficult for someone with depression. Here are a few things that you should try to avoid saying to someone with depression

1. “Things could be worse”

Of course, it’s tempting to encourage your loved one to look at the positive things in their life. It might feel as though if you could just remind them of all the good things, it would tip the balance, and they’d be happy again. But depression doesn’t work that way.

Depression doesn’t happen because someone weighed up the positive and negative aspects of their life and came to a decision. It’s a complicated illness with biological, genetic, environmental, and social components.[14]

Telling people with depression to “look on the bright side” or listing all the things they have going for them can make them feel more alone and even guilty. They’ve probably had that conversation with themselves and are frustrated that they can’t feel better.

It can also imply that depression is a choice or that they’re to blame for focusing on the wrong things or being ungrateful.

What to say instead: “I understand that it’s really hard to feel happiness or joy right now. I’m always here to listen anytime you want to talk.”

2. “Why don’t you just…”

Lots of things can help with depression, but pressuring your loved one to do something they’re not ready for or don’t feel able to do can leave them feeling worse rather than better. Try to avoid phrases such as “you should”, which imply that there is an easy solution that they’re just not doing.

Exercise is a great example of this. Exercise often helps people with depression,[15] but having depression makes your body less efficient at creating energy at a cellular level.[16] This makes it really hard to exercise. Being told to “just go for a run” when you’re in the middle of moderate or severe depression can feel as difficult as being told to “just fly to the moon.”

Recovering from depression is a slow process. Pushing them to leap in at a level they don’t have the resources for is unlikely to help.

What to say instead: “I can’t guarantee it’ll help, but if you’d like, we could go for a walk/cook something nutritious/try to find a therapist for you together.”

3. “I know exactly how you feel”

You’re probably trying to be supportive when you tell someone that you know exactly how they feel, but it can sometimes make them feel more isolated.

We never know exactly how another person is feeling and saying that we do risks trivializing their emotional pain. It can also make it harder for them to talk about what they’re going through if they think you’ve already formed your opinion about what’s going on for them.

What to say instead: “Everyone’s experience of depression is different, and I’m not going to pretend that I know exactly what you’re going through. I can relate to a lot of it though, and I’m here to listen.”

4. “Everyone goes through tough times”

Saying “everyone goes through tough times” might feel like you’re empathizing with your depressed loved one and also putting their feelings into a wider context. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to be what they hear.

To someone with depression, saying that everyone has problems tells them

- Their problems aren’t severe enough to justify their reaction (leading to self-blame and guilt)

- You might think that they’re faking/exaggerating (leading to feeling alone and misunderstood)

- They are to blame for their own illness (making it harder for them to ask for help)

- They shouldn’t talk about their feelings

- They are being selfish/self-centered

- They’re ‘just sad’ or ‘feeling down’ (which minimizes the severity of depression)

What to say instead: “Depression is an awful illness that affects lots of people. It’s absolutely not your fault. I’d like to see if there’s anything we can do to get you help, if that’s OK with you?”

5. “Why can’t you just snap out of it?”

Asking someone with depression to “just snap out of it” or to push through it minimizes the severity of their illness and makes it harder for them to seek or accept help.

Caring for a friend, family member, boyfriend, or girlfriend with clinical depression can be tiring and frustrating. This is especially true if they’re not ready to seek help or if they keep behaving in ways that you consider self-destructive, such as drinking too much or not looking after their physical health.

Even though it’s hard, try not to let your frustrations come out by making these kinds of comments. It’s usually better to turn to your support network to help you deal with your frustration and let you continue offering love and support to the depressed person.

In the words of one writer with depression, “I can’t try ‘not being depressed’ any more than someone else can try ‘not being tall’.”

What to say instead: “You don’t have to fight your depression alone. Some days will be better, and others will be worse, but I’ll be with you all the way.”

6. “You don’t look depressed”

It’s common for people with depression to try not to show the people around them how much they’re struggling.[17] This might be because they don’t want to worry people, feel embarrassed about how much they’re struggling, or not feel ready to admit to themselves that they have depression. They might also feel unworthy of care or worry that people will disbelieve them or think that they’re weak.

Although it might feel like a neutral statement of surprise to you, telling someone that they don’t look depressed can leave them feeling disbelieved. Trying to “pass” as healthy and hide signs of depression can be exhausting.[18] This can make it doubly hurtful when those efforts lead to disbelief on the part of family and friends. It also dismisses the huge courage they’ve just shown by opening up to you.

What to say instead: “I didn’t realize. Thank you so much for opening up. Would you like to talk about it?”

7. “Why can’t you just…”

It’s hard for someone not experiencing a depressive episode to understand how difficult it can be to carry out daily tasks. Things like brushing your teeth, opening the mail, or putting on outdoor clothes take almost no thought or energy for most of us. When you’re depressed, however, they can become a real drain on your resources.[19]

Try looking into Spoon Theory, which is used to explain one way that the world can seem different to people with an invisible illness or disability, including depression.

What to say instead: “Are there any tasks that I could take off your to-do list to make life easier?”

Types of depression

There are different types of depression. Although you won’t be diagnosing your loved one, it can be helpful to understand the differences. Here are some of the common types of depression.

- Major (clinical) depression: Also known as major depressive disorder (MDD). This is what most people are thinking of when they talk about depression. It is an extended period of depressive symptoms that can include sadness, anxiety, low energy, and disturbances in daily tasks such as sleeping and eating.[20]

- Bipolar disorder: Bipolar disorder (previously known as manic depression or sometimes bipolar depression) is characterized by periods of mania (unusually high mood, increased energy, enthusiasm for risk-taking) and episodes of depression.[21]

- Persistent depressive disorder (PDD): PDD is diagnosed when symptoms of depression have been present for more than two years. These symptoms will often be less severe than MDD, but because they are present for so long, they can have a dramatic impact on someone’s life.[22]

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD): SAD is a form of depression that seems to be linked to the amount of natural light we receive. It’s typically worse in the winter months, and symptoms reduce during the summer.[23]

- Peripartum depression: This used to be known as postpartum or postnatal depression, but it doesn’t only affect people after giving birth. Anyone who is pregnant or has recently given birth may have changes in their mood, but peripartum depression is more serious and can last for significantly longer.[24] There is increasing evidence that fathers can also suffer from peripartum depression.[25]

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): This is related to premenstrual syndrome (PMS), with symptoms clustered around the time of menstruation. The mood disturbances in PMDD, such as mood swings or severe sadness and anxiety, are more pronounced than in PMS and typically cause significant disruption to daily life.[26]

- Situational depression: This is very similar to clinical depression, but there is a clear ‘trigger’ for the feelings. This is usually a deeply stressful life event, such as the breakdown of a relationship or being the victim of a crime.[27]

Suicide prevention

No one likes to think that someone they love might be desperate enough to take their own life. Unfortunately, depression can lead people to feel that suicide is the only way to escape the way they are feeling.

If you think your loved one might be considering taking their own life, the most important thing is to broach the subject with them. It’s obviously scary, but asking lets them know that they can communicate honestly about how they’re feeling.

Be direct. If they say something like “It’d be better if I just wasn’t here” or “At least I won’t be a burden for much longer,” try asking them whether they mean that they are considering taking their own life. You could say “I’m not judging, but I do need to ask. Have you had thoughts about suicide? It’s OK to tell me if you have.”

You might worry that asking someone whether they’re suicidal might put the idea into their head. This is absolutely not the case. Research consistently shows that asking people about suicidal intentions decreases the probability of them making a suicide attempt.[28]

Warning signs of suicide

There’s a lot of stigma involved in talking about suicide, and this can make it difficult to know what you should be looking out for. Here are some of the key warning signs for suicide[29]

- Talking about suicide, even obliquely

- Talking or writing about death, dying, or suicide

- Making a plan for taking their own life

- Referring to themselves as a burden or suggesting that others would be better off without them

- A sudden sense of calm or energy following depression

- Having made previous suicide attempts

- Withdrawing from social support and activities

- Giving away possessions, making a will, or getting their affairs in order without any obvious reason

- Gathering resources for suicide, for example collecting pills or weapons

- Dangerous or self-destructive behavior

- Making arrangements for dependants or pets

Where to get help for someone who is suicidal

Try not to panic if you see one or more of these signs in your loved one. The most important thing is to reach out for help. Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 800-273-8255 24/7 for free, confidential advice.

For those outside of the United States, there is a list of suicide prevention hotlines here.

If you’re concerned that there is an immediate risk, don’t leave the person alone, try to remove dangerous objects such as medication, knives, or guns, and call 911.

How to look after yourself

Looking after someone you care about who is suffering from depression isn’t easy. It’s important for both of you that you also take good care of yourself.

Personal self-care can include things like:

- Taking time out just for yourself

- Making sure that your needs are met before helping your loved one

- Setting boundaries around what you can and can’t do to help

- Acknowledging that this is difficult for you as well

- Reaching out to your support network

- Finding a therapist or support group

Common questions

Why is it so hard to talk to someone about depression?

Talking about depression is difficult because it feels really personal and because we might not know how best to help the depressed person. We worry that we might say the wrong thing or make it worse. Rather than thinking about what to say, try to focus on listening and understanding.

Do people with depression have trouble communicating?

It can be hard for someone with depression to explain how they are feeling. They may have low energy or “brain fog,” which makes them think more slowly. They may also worry about being a burden on others, see little point in talking, or feel awkward because of mental health stigma.

Is there an online chat for depression?

Online chat for people with depression is available 24/7, as well as phone lines and text support. You can also find online therapy providers, such as Betterhelp. Helplines, such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, may be more appropriate in a crisis.